|

|

CompPanels:

Images from the Annals of Composition #37 |

|

|

It was 2003 and Jenny was sitting out in her garden, feeling depressed. Then, as she describes the event, "very slowly, the clouds formed into the word 'LOVE.'" She was amazed, she says. "It really touched me." A year later, Assalaam Wa Alaikum saw clouds against the moon forming the word "Allah." His family witnessed it also: "It was very clear and distinct." And a year after that, writing from Vancouver, British Columbia, a young man reported that "the clouds formed a perfect number 13 in the sky today." He was impressed: "It was radical, man!" People don't easily forget when the natural world, the world of dumb things, takes the shape of human language. The process doesn't contravene natural laws. Clouds, after all, assume a lot of different forms, some very like a whale. But when the shape is of script, even fragments of script, even individual letters, the event brings something of the numinous with it. The scar of a broken pine branch in Sinaloa, Mexico looks like a bleeding S, the very letter that begins the Greek word stigma; the cliffs of Dagor Mountain in Tibet, dear to Buddhists, manifest rock formations that look like Tibetan letters; the seeds in an eggplant being cut up for dinner, as happened once to Assalaam Wa Alaikum's mother-in-law, take the shape of "Allah" written in Arabic—and in these instances of found language the religious message is kin to the shiver we feel when we notice that a family of toadstools in the woods have arranged itself into a perfect letter O.

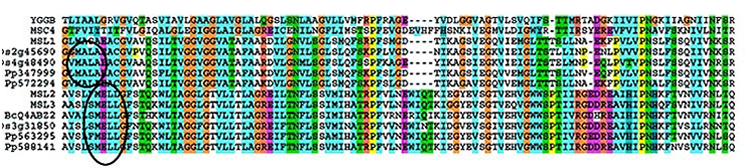

In March, 2006, a Caltech plant biologist was astonished to see that an alignment of protein sequences had arranged themselves into a personal message. She was studying the function of protein in mechanosensitive ion channels, and her computer was applying the standard genetics one-letter code for amino acid residues, where S stands for serine, V for valine, and so on (colors show patterns). But at one point this particular ion channel switched the code to English. As it turns out, the biologist has a colleague named Mala. "My friend Mala is not happy," she said, "but I think the universe wants her to use deodorant." |

||

|

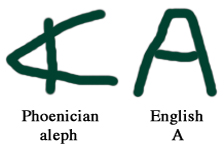

What does the universe want? The Phoenicians supposedly formed their letter aleph after the shape of an ox head (the Greek alpha, the Hebrew alef, and our Roman A may derive from the Phoenician aleph). In found language, nature returns the compliment. Flying geese say "V," merging rivers say "Y," and in the photograph at the left the scales on a butterfly wing say "A." Nature photographer Kjell Sandved tells how once in a Panama jungle he looked up and found himself eye to eye with a venemous snake draped over a branch. What he first noticed, he swears, was that the snake's body formed the letter Q. Since then he has travelled the world photographing natural forms that look like typographic symbols. His best known work is a poster of butterfly wings figuring forth all the letters of the Latin alphabet, including the A at the left. Or it is an aleph? Is this butterfly writing to us in English or Phoenician? One night in the 1670's, Arthur Dimmesdale "looked up to heaven and saw an immense letter A marked out in lines of dull red light." A couple of decades later—Wednesday, February 5, 1709, to be exact—somewhere in Russia "two large columns of fire were revealed, one in the east, the other in the west, and as they moved they formed the letter A." Yesterday or yesteryear, East or West, in fiction or in fact, humans want the nonhuman world to talk their language, even if only on occasion. In the Anglo-Saxon "Dream of the Rood" there is a moment that speaks for Christians and non-Christians alike, when one of our kind dies and all of nature weeps: "Wēop eal gesceaft." |

|

|

||

RH, May, 2006 |

|

|