|

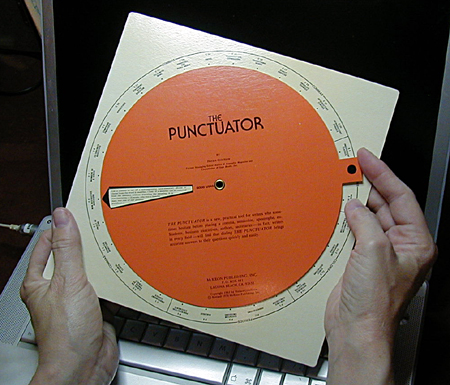

CompPanels: Images from the Annals of Composition #34 The Punctuator: A Grammar Volvelle |

And proper punctuation. Horace Critchlow's double-sided Punctuator was copyrighted in 1961 and revised in 1975. Point the wheel on the front side to an element of discourse (appositive, date, direct quotation, dialogue, etc.) and the revealed text provides the conventional punctuation of it. Point the wheel on the back side to a punctuation mark (dash, parentheses, quotation mark, italics, apostrophe, hyphen, etc.) and the revealed text provides the uses for it. The back side also expounds on types of sentences and parts of speech, exemplifies connectives and transitions, and lists seven steps to parse a sentence. All intended, as the front side says, quickly to answer questions posed by "students, business executives, authors, secretaries—in fact, writers in every field." It came in a handly plastic sleeve with holes to fit a three-ring binder. As far as I know, Horace Critchlow—whose name could have appeared in the dramatis personae of a Ben Jonson satire on grammarians—does not grace the annals of college composition. He worked as a publisher and editor. In 1940 he was a graduate student at the University of New Mexico when a new associate professor showed up with a Kelsey letterpress. It was Alan Swallow, who within a few years would acquire fame as an independent publisher of western literature and defender of small presses and little magazines. For two years Critchlow and Swallow tried their hand at the Kelsey press, printing vanity books and, under the rubric Sage Books, a few ventures of their own, such as early translations of three Spanish American poets (Neruda, Pellicer, and Andrade) and one of the first publications of Frank Waters. Then in 1942 Critchlow was drafted, and the next, and last, appearance I can find of him was as managing editor of the Author & Journalist magazine. What I know of volvelles all comes from Jessica Helfand's wonderful book, Reinventing the Wheel (New York: Princeton Architectual Press, 2002). Along with illustrations of many wheel charts through history (though she doesn't mention The Punctuator), Helfand stresses the functional similarity with computers, especially the way both allow the user to interact with the machinery. Isn't the volvelle a digital (though non-electric) generator of hypertext? RH, January 2006 |

Volvelles

or wheel charts have a long and distinguished history. The oldest surviving

one was made by the Spanish alchemist Raymond Lulli in 1306. It produces

astrological data as one piece of parchment rotates upon another, the

two held together by a thread. Astrolabes, planispheres (locating the

position of the stars from various geographical locations), and circular

slide rules work the same way—all common before the 19th century.

The heyday of the volvelle, however, was 1930-1960. Hand-held, die-cut,

made of cheap cardboard, wheel charts calculated every imaginable kind

of information: nuclear-bomb radiation levels, horoscopes, income tax,

time to castrate livestock, conversion from cocoa to chocolate, military

aircraft identification, range and yield of Soviet weapons, shotsize

to gun down wild animals, demographic data of countries world wide,

birthdate of country-music stars, handwriting analysis. . . .

Volvelles

or wheel charts have a long and distinguished history. The oldest surviving

one was made by the Spanish alchemist Raymond Lulli in 1306. It produces

astrological data as one piece of parchment rotates upon another, the

two held together by a thread. Astrolabes, planispheres (locating the

position of the stars from various geographical locations), and circular

slide rules work the same way—all common before the 19th century.

The heyday of the volvelle, however, was 1930-1960. Hand-held, die-cut,

made of cheap cardboard, wheel charts calculated every imaginable kind

of information: nuclear-bomb radiation levels, horoscopes, income tax,

time to castrate livestock, conversion from cocoa to chocolate, military

aircraft identification, range and yield of Soviet weapons, shotsize

to gun down wild animals, demographic data of countries world wide,

birthdate of country-music stars, handwriting analysis. . . .